The third and final workshop for the Illness as Fiction project was held at the University of Bristol on the 25th January 2019. Led by Dr Maria Vaccarella, the session consolidated many of the ideas explored in the previous workshops, and focused on Factitious Disorder, Fabricated or Induced Illness, and factitious HIV/AIDS narratives. My research considers the limitations of linear and triumphalist illness narrative conventions when expressing female autistic experience. As a regular participant in Maria’s workshops, I have been particularly interested in how factitious illness narratives appear to employ such conventions as a means to appeal to the reader’s empathetic faculties.

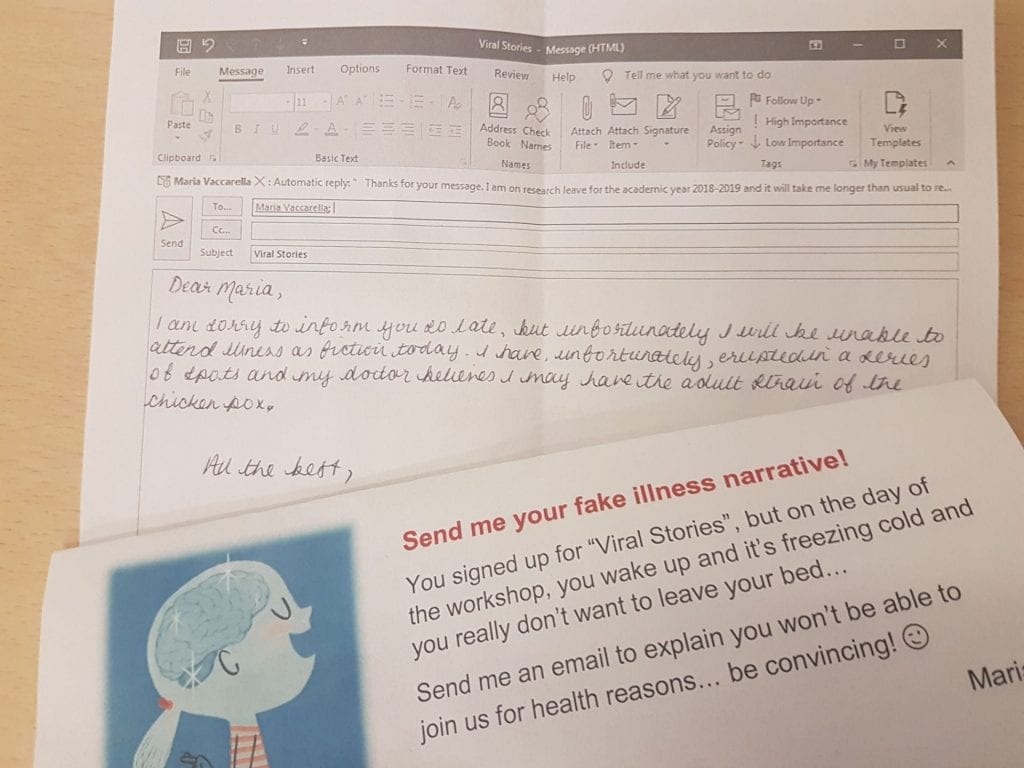

On this note, the ice-breaker exercise invited us to email Maria with a fake illness story, and explain why we were ‘missing’ the workshop.

Although it is unlikely that my effort was in any way believable, the task made me think a lot about how we talk about illness, and what kinds of literary devices may be used by those who do fabricate illness.

Maria began with an overview of the previous workshops and a project update, which included mention of Louise Benson James’s recent interview with Professor Lisa Bortolotti about the ERC-funded PERFECT project, and Maria’s upcoming presentation on Illness as Fiction at King’s College, London on the 27th February. She also provided us with an update on James Frey whose factitious memoir, A Million Little Pieces, was discussed in earlier workshops. Although his 2018 novel, Katerina, has garnered significant media coverage, Sian Cain of The Guardian has argued that, despite gaining fame through deception, writers like Frey continue to flourish by capitalising on such attention.

The morning session involved two presentations relating to factitious narratives of illness. The first talk was from Dr Christopher Bass, Consultant in Liaison Psychiatry in Oxford and expert in Factitious Disorder (Munchausen syndrome) and Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII, or Munchausen’s-by-proxy). Christopher discussed his experience of working with over 50 cases of FII, the condition in which an individual deliberately imposes illness upon another person, usually a child, and results in significant and lasting harm to the victim. He also referred to several high-profile cases, including the nurse Beverley Allitt who attacked 13 children (4 of whom were killed) for attention. By studying Allitt’s entire medical history, it was clear that her own Factitious Disorder had been transferred to her victims during the period of abuse. Although the perpetrator’s motives are unknowable and are inevitably complex, Christopher explained that the care-eliciting behaviour which characterises FII likely results from feelings of emptiness, and a need for care and attention.

Next, we heard from Dr Anita Lavorgna, who lectures in Criminology at the University of Southampton, and has written extensively on cybercrime and organised crime. Anita is investigating the potential harm of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM), which are approaches to illness developed outside of western medicine. Although proponents of CAM are not necessarily committing a crime, they partake in the act of ‘respectable deviancy’ because treatments are often untested, informed by pseudoscience, and are far more likely to harm than benefit the patient. Anita discussed the respectable deviancy of Belle Gibson, whose fabricated claim of cancer, and its management through diet and alternative medicine was investigated in Maria’s first workshop. Interestingly, as Gibson’s deviancy was exposed by online debunkers and eventually reached mainstream media, her narrative changed. Her constructed image of a mother, survivor, and businesswoman was replaced with a narrative of justification, and then of trauma, victimhood and a lack of responsibility. Anita also reflected on the problem of intervening in factitious narratives such as Gibson’s, due to the individual’s right to speak freely.

The talks incited vigorous and thought-provoking questions and discussion. Particular interest lay in the higher prevalence of women with FII, the slippery borderline between illness anxiety and deception, and the mental health issues which often accompany FII. We also considered respectable deviancy in relation to the ‘anti-vax’ movement, and how media articles relating to CAM often, problematically, present doctor and celebrity opinions with equal credibility. With so many fascinating strands of enquiry, it was unsurprising that we ended up running into the break!

The afternoon consisted of collaborative activity and roundtable discussions. Returning to Susan Sontag’s claim that cancer and HIV/AIDS are especially prone to metaphorical distortion, Maria explained how HIV/AIDS has been perceived in terms of contagion and subversion, ‘something total, civilisation threatening’ (Sontag, 1989, p. 149). We were presented with a series of passages from HIV/AIDS literature to explore the boundaries between memoir and the novel. With autofiction also entering the mix, it was a challenging task! It did, however, provide valuable insight into how particular approaches to narrating illness influence both literary forms. Maria explained how these narratives have changed in light of medical advancements, and that it can be difficult to reconcile the graphic descriptions from the 1980s with today’s experience, where a person living with HIV may appear physically fit, but often hides the trauma of having witnessed many deaths in their community. She was also keen to remind us that, although we concentrate on singular examples, the history of AIDS is also the unprecedented history of communities coming together.

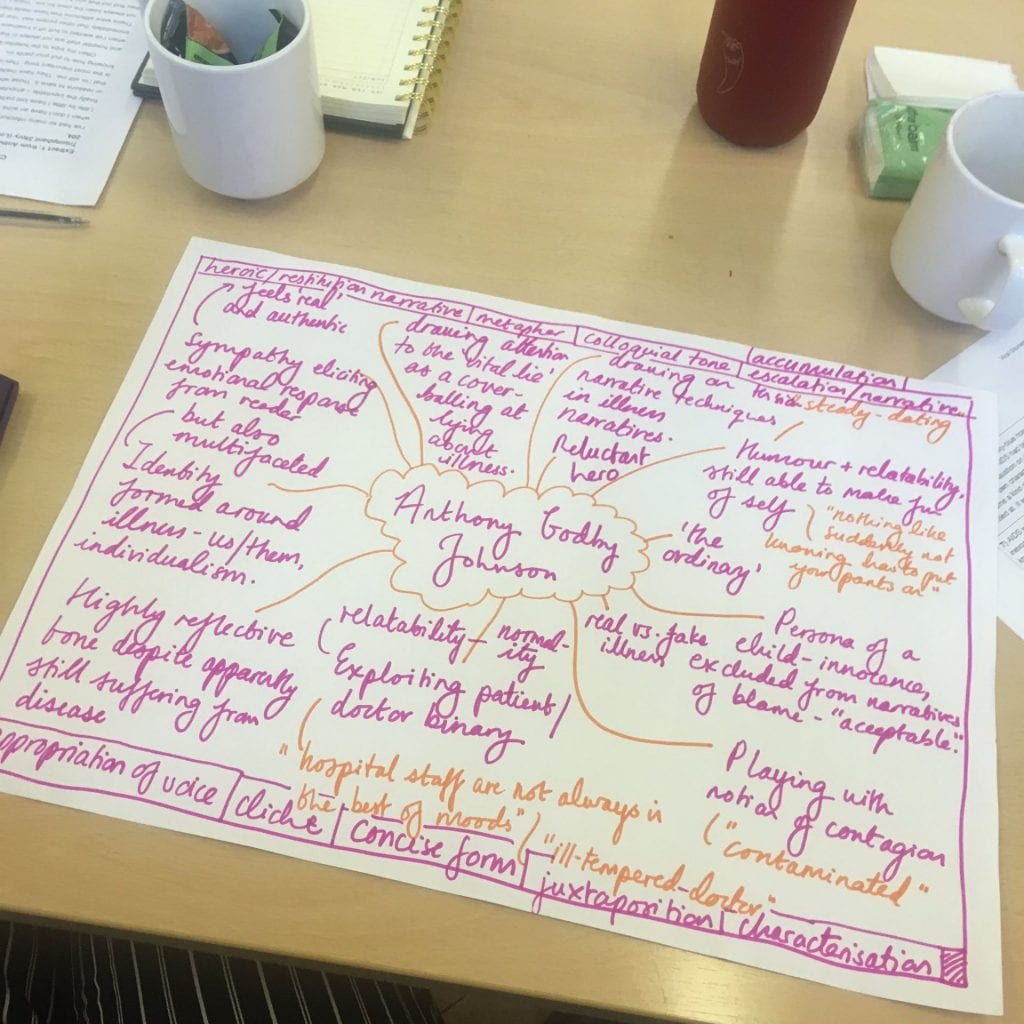

It was with a natural progression, then, that we discussed HIV/AIDS in the context of a literary community. We learned about Anthony Godby Johnson’s narrative, A Rock and a Hard Place: One Boy’s Triumphant Story (1993), which attracted attention and support from prominent HIV/AIDS activists. However, not only was the story revealed to be completely fabricated, it was also apparent that Anthony was a fictional creation of Joanne Vicki Fraginals who claimed to be his adoptive mother, ‘Vicki Johnson’. Consequently, Johnson’s narrative reveals a curious instance of virtual Munchausen’s-by-proxy. Maria’s engagement with Anne Rothe’s interpretation of Johnson’s case was particularly interesting. In Popular Trauma Culture: Selling the Pain of Others in Mass Media, Rothe suggests that, with the interest of real-life writers in ‘Anthony’ and his later emergence as an online persona by a second perpetrator, this instance of FII has become a kind of literary work in itself (2011, p. 128).

Our final task was to consider the memoir and Armistead Maulpin’s rewriting of Fraginals’s deception, The Night Listener (2000). We located literary devices which facilitate an emotional experience that offers, in the words of Alyson Milner, ‘a different kind of real’ (2012, p. 96). This led to discussions about how the writers attempt to elicit empathetic responses through notions of innocence, doctor/patient relationships, stigma, and the representation of the self as ‘normal’ despite being ill.

It was with a thought-provoking end to the workshop, then, that discussion turned to consider the expression of illness more widely. It brought into sharp relief the ways in which we communicate illness to medical professionals, our peers and in literature, and how notions of judgement or disbelief may influence such expression.